In 2015, I traveled to San Fransisco with my family for the first time. While we walked through San Fransisco's Chinatown to find a good restaurant, I noticed a darker side to the city: there were shocking amounts of elderly Asian-Americans walking around the streets, collecting trash and empty bottles. What hurt me the most was seeing their frail figures lugging around towers of cans and cardboard while passersby simply stepped around them. Maybe that's just the way it is, but it led me to wonder: what's being done to help these impoverished Asian-Americans? And just how much of the Asian-American population is low-income? In the midst of my research, I contacted organizations that are dedicated to relieving Asian-American poverty and asked them about what they've learned throughout their work. Below is the interview I conducted with Mr. Howard Shih, Research and Policy Director at the Asian American Federation in New York City. 1. Can you explain a bit about what exactly this organization does?Howard Shih: "The Asian American Federation is sort of like an umbrella organization for over 70 Asian-American agencies in New York City. We use research to justify our policies, so we have essentially advocacy rooted in numbers. We do this by providing case studies of families who are in need, and by providing support to those families, such as mental health services or leadership development." 2. What would you say are some of the major problems the Asian-American community in NYC is facing? Research and Policy Director at the Asian American Federation, Howard Shih Research and Policy Director at the Asian American Federation, Howard Shih Howard Shih: "Well, poverty affects all Asian ethnicities in New York City. There are certain ethnicities who we do see higher levels of poverty in. The Bangladeshi-Pakistanis, Chinese, and recently, a spike in the Burmese refugees. We see that there are more and more parents working multiple jobs, there's overcrowded housing--there's a lot of Asian-Americans in public housing in East Harlem. And there's people asking "why are there Asians in public housing?" Well, it's because they're poor, I mean why else. Why is it strange that Asians need to turn to public housing? The stereotypes surrounding Asians are perpetuating the idea that we're all doctors, lawyers. That's not the case. And there are those who do fit into those stereotypes, but there's a large portion of those who don't." 3. Based on your research, are Asian immigrants getting equal access to the kinds of opportunities that others are getting?Howard Shih: "I would say that language access is the hardest for these families. There is not enough availability of translated materials, for example, many parents are struggling to help their kids apply to high schools in the city because they don't understand the application materials. The children are then affected by this because they now have to translate for their parents. They aren't prepared for the stress, and this may take a toll on them in the future. We also see a flipping of the social order. You know, elders who have all this knowledge of the world are no longer able to navigate the communities they are in, and it becomes the young people who become knowledgeable. This turns into social tension for the community." 4. How do you think the coronavirus has impacted Asian-American communities?Howard Shih: "There's definitely been raised fear about hate crimes. We're trying to set up safe platforms for affected people to speak out and report incidents, but you know there's a lot of people who are reluctant to report them because they aren't registered in the U.S., so it's a struggle to get them to feel safe in reporting hate crimes. Furthermore, the kids are affected because those who are under-resourced are not able to engage in remote learning, and small businesses--especially Asian ones--are really being very impacted. There's always been some avoidance of Asian restaurants and grocery stores, but now they're being impacted more than ever." 5. What are your thoughts on Asian-American stereotypes that are being perpetuated in the media today?Howard Shih: "They definitely, as you said like in "Crazy Rich Asians", promote the idea that Asian-Americans don't face issues like poverty and lack of education. There are consequences to these generalizations. The Asian-American community in New York City is close to 16-17% of the city's population, but only 2% of the city's social contracts go to Asian-American organizations. There is a much higher demand than there is output." 6. Do you have any thoughts you'd like to share that may raise awareness on the struggles Asian-American families are facing? Howard Shih: "Not exactly final thoughts... but just, see us. Who we really are. Behind all the stereotypes, and the media representations." Author: Carina Sun

0 Comments

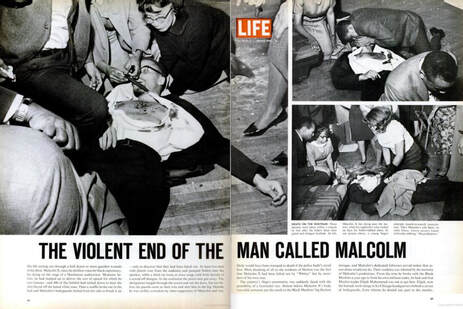

Starting in late elementary school, I noticed that slowly, everyone began packing lunches. I don't know if it was a "cool" thing to not eat the bouncy popcorn chicken from the school cafeteria, but soon, if you weren't packing lunch--you became "uncool". The other kids I sat with would bring peanut-butter and jelly sandwiches, juice boxes, and lunchables. I would bring thermoses of leftover fried rice, dumplings, and noodles. At first, I was excited to start packing lunches and bringing them to school. I could finally show my friends what authentic Chinese food tasted like--not the "Americanized", super-sweet stuff they sell at Chinese takeout places. However, I remember so clearly the day I brought a lunch of some leftover rice and Mapo tofu, a student made a comment: "What's that smell?" Everyone was scrunching their noses, looking for the culprit who had brought something strange-smelling to the lunch table. I had never felt so out of place than in that moment, sitting there with my rice and pungent tofu whilst my friends had sandwiches and salads. I remember the burning feeling under my cheeks as I silently closed the thermos and sat there the rest of lunch, drinking water. I was ashamed. After that day, I stopped bringing Chinese food to lunch. I convinced my mom to go out and buy lunchables for me, and would wake up extra early in the mornings to make sandwiches. One day, my mom slipped a packet of my favorite octopus jerky (which to be fair, did smell nasty but tasted good) into my lunchbox. At lunchtime, I opened my lunchbox to find the smell of octopus jerky wafting into my face. Everyone suddenly turned to me, scrunching their noses and asking what on earth I had packed. Trying to fit in, I explained that I had brought it in as a joke--a disgusting snack to dare them to try. I handed out bits of my favorite snack and told everyone to try it, lying that it was my least favorite food ever. Soon, everyone was laughing and spitting out the octopus jerky, and I felt so relieved. Why should I have lied about the things in my culture that I liked just to fit in with those who couldn't appreciate it? My elementary school self was so focused on fitting in that I had pushed away everything about myself to fit the mold of a "normal student" in suburban Pennsylvania. As I've grown up, I've realized that the world is too big to focus on fitting in. As social media has played a more prominent role in everyone's lives, I've been exposed to an online community of Asian-Americans who faced the same lack of self-confidence, but also a community of people who are able to build each other up. This awareness has been a big confidence booster, and all the new people I've met have helped me to overcome my inferiority-complex to become a more-confident version of myself. If I could tell my elementary school self something, it would be that there is a whole world out there full of open-minded, supportive people who may be facing the same problems you are. Focus on finding those people, and build each other up. Also, ham and cheese sandwiches are nasty. Author: Carina Sun  "Yuri Kochiyama", image credits to original owner. "Yuri Kochiyama", image credits to original owner. In recent years, the term "Asian-American" has become widely popularized and accepted. However, there are still many people who do not accept this term, stating that you can only be one or the other. This absurd notion has been around since long before recent events surrounding the coronavirus. It may have stemmed from the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Or perhaps it was driven by the Japanese internment camps during World War II. Either way, the history of Asian-American discrimination has been long and painful. Like us here at Declarasian, there have also been many Asian-American activists throughout history as well. Their efforts made it possible for us to be where we are today, and for America to become a more progressive nation. One of these activists I have recently stumbled across is Yuri Kochiyama, a Japanese-American who was an activist during World War II, when Japanese internment camps began appearing. These Japanese internment camps are rarely acknowledged in school history lessons, as it was a dark time in America's history. During WWII, these camps held over 120,000 Japanese-Americans. Yuri spent most of her childhood in Los Angeles with her family, but they were forced to relocate to internment camps after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Her experience there, and her brief friendship with activist, Malcolm X, inspired her to stand up for not only Japanese-American rights, but also black rights. She wanted to advocate for equality among all races, something that separates her from other Asian-American activists. During the 1960s, Kochiyama propelled the Civil Rights Movement by hosting open houses with her husband, often gathering more than a hundred people at each one. She began inviting strangers to speak at these open houses, and she also began advocating for Harlem students to get equal education opportunities by joining the Harlem Freedom School. Perhaps her most famous moment was by the side of Malcolm X when he was assassinated. She cradled him in her arms as he took his last breaths.

for equal opportunities for all races stems far from the above mentioned. After the Japanese-American internment camps ceased to be utilized, she advocated with her husband for reparations and a government-issued apology to all those who suffered in them. Her efforts were acknowledged when President Ronald Reagan signed into effect the Civil Liberties Act in 1988.

Throughout her lifetime, Kochiyama worked tirelessly towards her purpose and desire to promote social and human rights. Her work is not forgotten today, and has continued to inspire young activists like ourselves to continue fighting for equal human rights to this day. As the Asian communities not just in America but around the world face ever-increasing rates of hate crimes and xenophobic actions, it's more crucial than ever to remind ourselves that we too, can stand up in the face of these situations and change the world. In the words of Kochiyama herself, "the movement is contagious, and the people in it are the ones who pass on the spirit." Author: Carina Sun Sources: https://caamedia.org/blog/2014/08/29/yuri-kochiyamas-words-of-wisdom/ https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2014/06/06/honoring-legacy-yuri-kochiyama https://blogs.brown.edu/ethn-1890v-s01-fall-2016/historical-figures-and-organizations/yuri-kochiyama/ https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Yuri_Kochiyama/ |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed